INTERVIEW // AFRICAN VISUAL STORYTELLER

NADER ADEM – POWERFUL PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY

Interview by Aida Glowik

Published January 20, 2022

Instagram: @africanvisualstoryteller

ARTIST BIO

Nader is a portrait and documentary photographer from Ethiopia.

Website: www.naderadem.com

Instagram: @naderphoto

1. Can you please share what drew you to portrait and documentary photography?

What is the heart / intention behind the work that you do?

I loved portrait and documentary photos since my early days in photography. For me, portrait is about capturing a stunning and emotive image of human faces that evokes feelings in the viewers. I use portraits as part of a story aiming to captivate the viewer attention to know or understand the story. Sometimes I took the portraits while on the road or daily walking where I get attracted and stop to shoot.

Documentary is a way for me to document the real life struggles, details, and moments that we may be missing while busy with our own struggles. In my works, I search for untold stories that I don’t see in the Ethiopian photography and through that I’m trying to show unseen life, to change perspectives or social stereotyping, such as disability in “Life as a Disable Person” or Muslim community in “Anajina”.

2. Do you believe that the eyes are the key to truly powerful portraits? If so, can you expand on this notion?

Yes, I do. There is a saying that “the eyes are the window to the soul.” The eyes are the most important part of the portraits as they are the most visually expressive tool, reflecting true essence of the subject and revealing what is within. In my portraits, I usually focus on having the subjects directly gaze at the camera, as that is also captivating and make the viewer connected to the subject.

3. Can you share how it is working with people as a deaf photographer? How do you go about communicating with and bringing out raw emotions from your subjects?

Deafness affects my photography in two ways. I face some difficulties in communicating with people directly. My sister often assists me in interpreting and communicating with people. The difficulties in portrait or street photos is when people agree to stop and allow me to take their photos, especially in the rural area, but I can’t get their stories. I wish I could communicate with them to ask questions and know more about them.

On the other side, I think deafness has given me an advantage – to have a better eye when taking photos. I am not distracted by noises and more attuned to body languages and give attention to little details that others may tend to overlook. I give more attention to what I see in the faces, not what they say or do, especially with the eyes as it is an honest tool that does not lie and people can’t control it.

Sometimes, I notice that people can’t comprehend the idea of a deaf photographer or that a deaf person is able to produce good works. I think that might be due to misperception and stereotyping associated with deaf people in the Ethiopian society. I understand that and try as much as I can in my work to make sure that that they are comfortable, showing them the photos in my camera, asking what they think and making connection using nonverbal communication.

4. There are a number of elements that contribute to creating a powerful portrait, which include, but are not limited to: lighting, composition, emotions and technical approach.

Which of these do you utilize the most in your work? And why?

Any good portrait is a result of A combination of all these elements that you mentioned. I usually try to experiment with portrait photography using different angles and lighting. But the most important element for me is lighting. I tend to use natural light as much as I can. Lighting helps show great details on human faces and can reflect different results.

5. Ethical representation of individuals and communities is paramount in this work. Can you shortly explain your process of making sure that you are depicting your subjects accurately and maintaining their dignity?

Ethical representation is one of the basic principles that I abide by in my works. I always keep in mind when shooting in Ethiopia that I show a community that I am part of. So I make sure that they are respected, portrayed accurately and in dignifying way.

First step is to get subjects consent to take their photos, letting them know clearly what the photos will be used for. Then, I make sure to represent people as accurately possible, avoiding the stereotypes and anything that may diminish how they are perceived by the viewers. I also make sure to take into account that I should respect and understand local traditions and customs; even if I have to ask sometimes to avoid any misunderstanding.

6. Over the years, photographs have played a significant role in perpetuating negative stereotypes and contributing to false narratives of Africans. In your opinion, what steps should be taken to right these wrongs?

African photographers already start changing the distorted image of our continent mainly through social media platforms. Though challenging, these platforms present a tremendous opportunity that African photographers are increasingly using to transform the stereotyping and misperception set by the other media about Africa. You can see platforms such as Everyday Africa, which show images by photographers living and working in Africa – presenting the reality and the beauty of Africa. COVID-19 also presented an opportunity as it created the need by western media for photographers on the ground to document situations in Africa, and they produce different and great works.

These are encouraging developments so far but I think there is need for more to be done by the African countries. First of all, there is a need for understanding the importance of photography as it relates to global representation, providing a good supportive environment for photographers and investing by governments in developing institutions, or organizations that support emerging photographers and produce new skills. You can see a great example in DESTA for Africa Foundation and Addis Foto Fest, by Aida Muluneh.

7. What is your viewpoint on having more African photographers telling African stories?

I think we need more African photographers in today’s world more than ever to tell Africa’s true stories and rectify its distorted image. We are living in a world where photos become a powerful instrument in creating perceptions and changing reality. I believe African photographers will tell African stories more accurately, with dignity and good intention. In comparison to others, they have the advantage of cultural background and they are a part of the societies that they are documenting in their photos.

8. One of the most renowned projects that you worked on is focused on Anajina, a pilgrimage site for Muslims visited by thousands of people from all over Ethiopia. As an Ethiopian and someone of the Muslim faith, can you share how you were able to visually tell this story more authentically as opposed to someone coming from the outside that does not have that kind of insight and connection?

“Anajina” is one of my favorite works. It took me some time to do it. I planned it in mid-2016 and did it during August 2017 as I was waiting for the celebration time at the site, where thousands of people from many parts of Ethiopia flock twice a year there.

I was driven by the desire to tell untold story about a Muslim community that I don’t see much of in the Ethiopian photography and about a place that is a symbol of Sufism, with charming architectural and social values representing cultural diversity in Ethiopia. I think I might be the first Ethiopian photographer to shoot this site because during my research, I found that it has been shot by foreign photographers but not Ethiopians.

Being an Ethiopian and Muslim may have contributed to the story as I shot with better understanding of the eminence value of this site for the pilgrims and the meaning of simple acts such as kissing the tomb or covering their face with the site’s white sand, and these religious rituals aiming blessings and spiritual renewal.

9. Let’s say, ten years from now, what are your hopes and dreams for this industry and the work it produces?

I hope to see many positive changes for photography in Ethiopia. First of all, I hope after ten years that the Ethiopian society will have a better understanding of photography as a form of art expression, not only for weddings and occasions. I hope that photographers will have an encouraging environment to produce world-class works, not seen suspiciously by the society, given the same level of respect and access as foreigner photographers, and have a professional association and regulations that support and regulate the industry in Ethiopia.

I also hope to see an institution that provides formal education on photography, which will help a lot of emerging photographers. You can see a number of schools or educational programs in other African countries producing talented photographers but none in Ethiopia, as far as I know. Ethiopia has the largest photo festival in east Africa thanks to Aida Muluneh and (DFA), which provides a platform for Ethiopian works to be shown alongside international works. I think education will help a lot in development of Ethiopian photography works.

A heartfealt thank you to Nader for taking part in this interview.

Please share this interview with your friends and family. Instagram: @africanvisualstoryteller

– Aida Glowik, Photographer & Founder of African Visual Storyteller

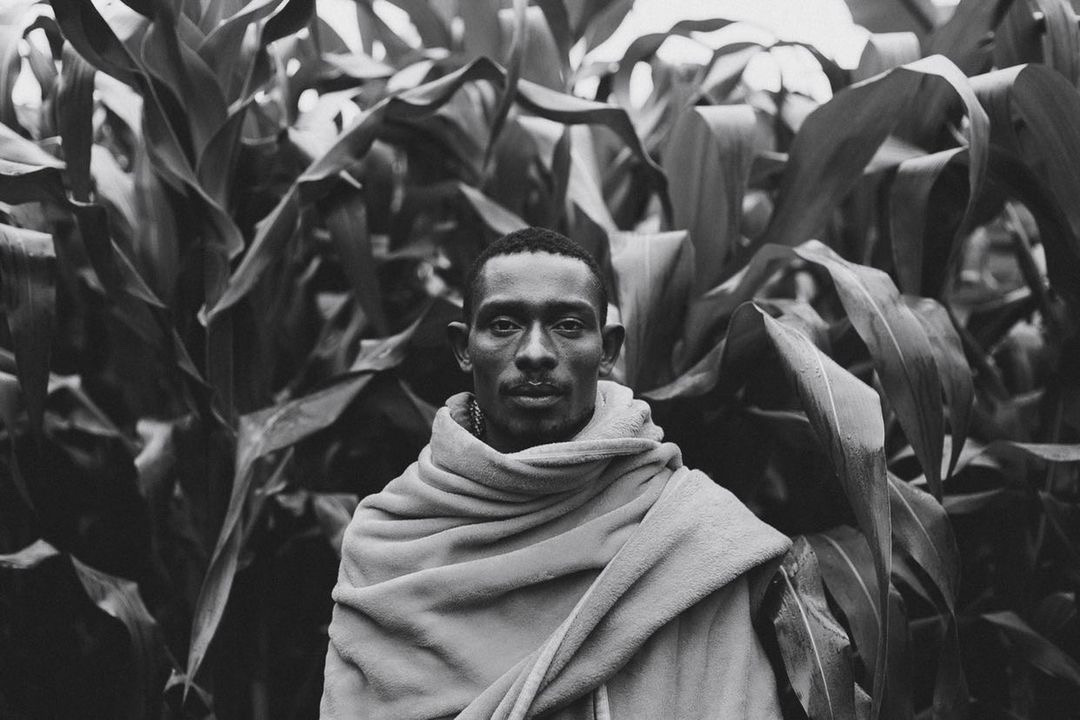

Images from “Anajina” by Nader Adem

“Thousands of people from many parts of Ethiopia flock twice a year to “Anajina” to pray to God and be part of religious rituals seeking blessings and spiritual renewal. Anajina, as known in the Oromo language, or “Dire Sheikh Hussein”, is a sacred site in Bale, southeastern Ethiopia. Dating back to the 12th century, it is named after an influential Muslim scholar called Sheikh Nur Hussein, reputed for his religious teachings and miraculous deeds. The site is a place of pilgrimage, a symbol of Sufism, and of aesthetic architectural and social values representing cultural diversity in Ethiopia. However, it is facing a great threat from those who espouse a more puritan version of Islam, amid growing Wahhabism influence in the region. Shot on August 2017, long shots & portraiture, this series documented Anajina’s unique religious and cultural heritage as it has existed for centuries in this part of Ethiopia.” – Nader Adem

Photographs in this article by: Nader Adem.